A once-thought impossible work for cello

The precipice of solo cello repertoire.

Prokofiev’s Sinfonia Concertante, Op. 125 (otherwise known as Symphony-Concerto for Cello and Orchestra), has become a staple of the solo cello repertoire. For those familiar with this colorful and dramatic work, it may be surprising to learn it was not always the success story it is today. The bones of the Sinfonia Concertante belong to an earlier Prokofiev work: his Cello Concerto No. 1, Op. 58, and by no means was this a favorable piece in its time. Following its 1938 premiere, music critics received the piece with such negativity that Prokofiev withdrew it from publication.

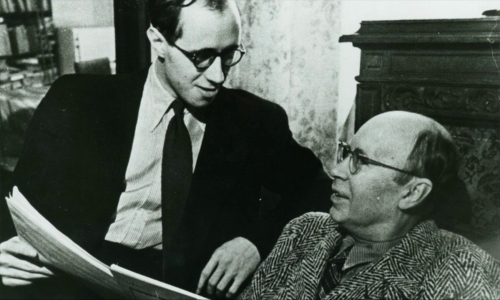

In a twist of fate, a young cellist somehow obtained a copy of the score years later. The cellist included the work during a public performance at Moscow Conservatory’s Small Hall. Prokofiev, shocked that a cellist sought to perform the piece, ensured he was in attendance for the performance. The young cellist performed the work with such passion and masterful technique that Prokofiev approached the soloist after the concert and offered to revise the concerto for him. The cellist agreed, and as time passed, became heavily invested in the project, often providing reference as to the capabilities of the cello as an instrument.

This young cellist was not any average conservatory student; Prokofiev’s collaborator was none other than the legendary cellist, Mstislav Rostropovich. This is to say that Rostropovich’s technical prowess on his instrument was far more advanced than Prokofiev likely anticipated. It may be because of this quirk that Prokofiev was more eager to write musical passages that were highly demanding of the performer’s abilities.

By its modern definition, a concerto is a work for a solo instrument with accompaniment, that often includes an extensive and virtuosic part for the soloist. But the revised concerto that Prokofiev wrote went above and beyond what composers of his time deemed “virtuosic”. Wild extended passages of unaccompanied solo performance (called cadenzas) take the performer up and down the entire range of the cello, calls for playing across all four strings simultaneously, and is sometimes notated across two separate musical staves.

During the rehearsal for the premiere of the revised work, Rostropovich often overheard the orchestra members mocking the writing of the solo part—calling it “unplayable and dissonant”. Because Rostropovich was able to flawlessly execute the solo part, Prokofiev’s final revisions only included changes to the orchestra’s writing by easing up on the demands of the orchestration.

Prokofiev revised the piece until the day he passed on March 5, 1953. It’s difficult to say whether he would have continued to revise the work, but the final iteration of the Sinfonia Concertante was immortalized with a performance by Rostropovich in 1954.

Many years passed and few cellists other than Rostropovich dared to perform the work, but as years passed, the technical prowess of young cellists grew stronger. Today, the work is often heard being performed during prestigious string competitions, especially its devilish second movement. During the 2024 Stulberg String Competition, sixteen-year-old Joshua Kováč performed the Sinfonia Concertante, winning him the Silver Medal.

As part of his prize, Joshua will return to Kalamazoo on Sunday, October 6 performing the Sinfonia Concertante alongside Western Michigan University’s Symphony Orchestra. To hear Joshua perform this breathtaking work live, join us for the performance at Miller Auditorium, beginning at 3:00 P.M. EST. Tickets are available at stulberg.com/events.